Each installment of this miniseries addresses some aspect of the series questions posed in part 1. This episode touches on potential problems, differences in theory and practice, and hence has relevance for ethics, competency, and training differences. The scope of these briefs is limited to allow exploration of essential features rather than being a comprehensive, in-depth exploration.

Series Questions to Consider

• What should we consider regarding ethical use of sand, principles and best practice guidance?

• What is the role of the clinician using sand and symbols with clients?

• What clinician preparation; professional-theoretical preferences, attitudes, and perceptual ability are essential for clinician use of sand?

• What are the key distinctions in theory and practice among sand therapies?

Sand therapy and its various theoretical approaches add a rich and beneficial component to a clinician’s ability to conceptualize, comprehend, and respond to his/ her clients. Competency with specific approaches to sand therapy will vary significantly. Because of this preparation, attitude, clinical insights, interventions, and training will vary in quite significant ways. Clinician ability with sand relies on theory, philosophical roots, a specific skill set, and a clearly defined role of the therapist. The enormous difference in clinician ability is one reason we must be careful with terminology, claims of efficacy, training, ethical parameters, and use.

Theory provides the framework that defines therapist perspective and interventions which can make a substantial difference in client experience. Work with sand and symbols often complements a therapist’s primary theoretical leaning which may include trauma work, family systems, mindfulness, positive psychology, therapeutic metaphors, analytic analysis, and various cognitive, humanistic, and post-modern approaches. However, a therapist schooled solely in pre-mindful cognitive-behavior interventions must be exceptionally careful to avoid defaulting to behavioral directives, questioning, attitude, and interventions since work with sand therapy, a projective technique, is complex requiring special boundaries and safety from therapist projections. Clinician curiosity, sense of power, and the drive toward instruction can easily cause the therapist to cross appropriate boundaries. On the other hand, many will handle this more gracefully, such as a trained art therapist, a practitioner of Milton Erickson’s therapeutic metaphors, clinicians who are well-practiced in mindfulness, and those skilled in Jungian process will have perhaps greater ease. This flows from a practiced intuitive resonance with symbol meanings, and well-honed witnessing and containment abilities when using sand.

Sand therapy is a wonderful play therapy approach that engages the imagination of clinician and client, and is fairly flexible regarding theoretical leaning. However, nomenclature is sometimes confusing. The terms Sandplay and sandtray are often used interchangeably and this is problematic if we wish to keep the integrity of the process. For example, Sandplay therapists take extensive training in Jungian conceptualization of symbols in sand, and they complete a series of personal sand scenes often taking a year or two. To use the term Sandplay implies that one has this specialized background. Sandtray, an American appropriation of Sandplay, most often relies on Rogerian Person-Centered or Adlerian perspectives to conceptualize the client’s work in sand. No training or personal process is required with sand but the clinician may be highly skilled in Person-Centered therapy.

One particular problem, more serious than nomenclature is authority. For example, too often clinics and mental health agencies encourage masters’ level interns to use sandtray with clients without prior training. There are several issues. An intern’s early perception and experience with one population will have no comparative basis for grasping important differences with other populations and problems; lack of a well-informed foundation gives ways to bias and assumptions about the purpose and process for using sand; open-ended permission from clinical authority (supervisors, licensing agencies, clinical directors) can leave the impression that use of sand without significant training is acceptable and efficacious. Permission once given to encourage intern exploration without authorial stipulations to obtain real grounding in the use of sand leaves open the door to use sand in future practice with no challenge to clinician suppositions and clinical habits. We’ve set a precedent for potential misuse.

Besides nomenclature and misjudgment of authority another gap to address is the practice of continuing education. Clinicians, pressed with an exhausting schedule, intense cases, and little self-care must organize their quite limited time to obtain required credits toward their license. The rich array of offerings in conferences and local trainings are a great support for continued growth. It all makes sense if we don’t look too closely at the implications. Continuing education courses, online and face-to-face, are supposed to support professional development within certain parameters. The ideal centers on therapists learning new interventions, ethics and best practices, obtain needed credits, and leave the experience rejuvenated. Presenters have an opportunity to offer emerging ideas, and professional associations bring in a financial base to continue. Everyone should be happy. But there is a gap in this process when it comes to sand therapy. A one-day conference presentation or workshop can be an excellent introduction. However, time is simply not available to present critical aspects of theory, ethics, complex practice skills, and a safe private in-depth experience of their own. When using sand therapy much more is involved, and essential to support clinician competency and his/her capacity to conceptualize, comprehend, and respond to clients and their sand scenes.

Sand and symbols opens the way for representations trauma, of client grief and loss, especially those experiences most difficult to share with others; the experience and emotions for which one is unable to speak. The client places images in the sand tray while the facilitator keeps a mostly silent, safe, mindful presence, a highly tuned resonance with the emerging images and the client. If the client chooses to share parts of his/her sand scene the facilitator must be a trusted witness, listen with care for layers of meaning, remain in the present, honing immediacy to resonate more fully -- in a stillness that attends to the tone and tenor of the sand scene and client story. The clinician is witness and guardian, acknowledging the deeply felt experience of the client – and ways they themselves are moved. The process is empowering, honoring grief and layers of loss as well as the client’s special strengths and unique story. We are the gatekeepers for the integrity and safety of this process. It is through our own immersion we gain insight, the ability to resonate with client and sand scene, strengthen our boundaries, and validate the healer within.

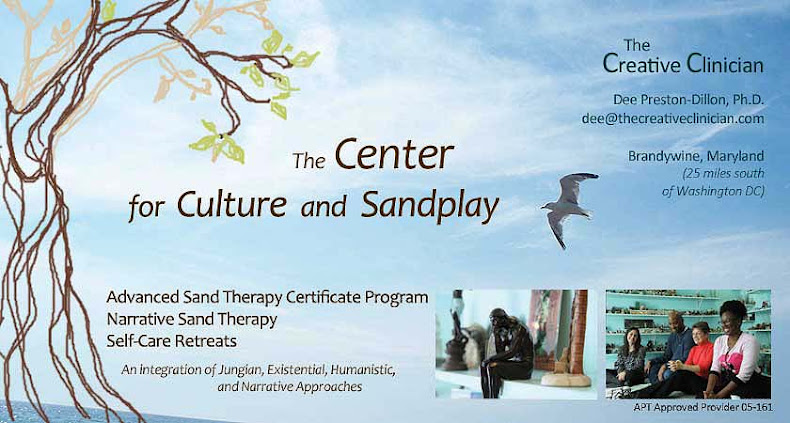

Dee Preston-Dillon, Ph.D.

The Center for Culture and Sandplay, Brandywine Studio

dee@thecreativeclinician.com

The Center for Culture and Sandplay Brandywine Studio

A Space Created for clinicians . . . .

Staff Retreats . . . . Small Cohort Group Training . . . . Self-Care Consultations . . . Private and On-Site Consultations . . . . Graduate Student Groups

©Dee Preston-Dillon, Ph.D. All Rights Reserved.

To share article, please use a link directly to this site. Other sharing prohibited.